R&D Strategies for T Cell Engager Drugs

From hematologic malignancies to solid tumors

Introduction:

Amid a surge of advancements in immunotherapy, T cell engager (TCE) therapy has emerged as one of the most promising treatments, following the success of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and CAR-T therapy. With its unique “precision strike” mechanism and substantial therapeutic potential, TCE therapy is providing new hope for patients with cancer and autoimmune diseases.

The development of TCE drugs, which initially focused on targeting B cell-related antigens (such as CD19 and CD20) in hematologic malignancies, has now expanded to include tumor-associated antigens (TAA) in solid tumors. Additionally, TCEs have demonstrated therapeutic potential in autoimmune diseases. This article will provide an in-depth overview of TCE therapy, including its mechanism of action, clinical landscape, and research and development strategies.

Mechanism of action (MOA) of TCEs

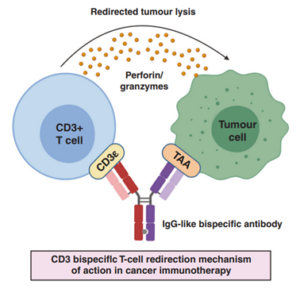

TCEs refer to a class of bispecific or multi-specific antibodies, typically composed of two antibody or antibody fragments forming two arms. One arm targets TAAs on the surface of cancer cells, such as CD19, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), and delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3). The other arm binds to the CD3 molecule on T cells. By promoting the formation of an immune synapse, TCEs can directly activate T cells to release cytotoxic molecules such as perforin and granzymes, efficiently lysing tumor cells (Figure 1), without requiring the involvement of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). This unique mechanism enables TCEs to recruit all available T cells via CD3. As a result, TCEs are effective at low doses, not dependent on the tumor’s inherent immunogenicity, able to overcome immune-escape mechanisms like tumor cell MHC downregulation, and are relatively simple to manufacture [1].

Figure 1. MOA of TCEs [1]

Classification of TCEs

Based on structure and MOA, TCEs can be broadly divided into two major categories: Fc-containing and Fc-free.

- Fc-containing TCEs: These have longer half-lives and greater stability, but an intact Fc may impede T-cell trafficking and limit anti-tumor activity. Fc-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) can also trigger unwanted non-specific immune reactions in vivo [2].

- Fc-free TCEs: These are smaller in size, with improved diffusion and tissue penetration and potentially lower clinical dosing, but they have shorter plasma half-lives. Common representatives include nanobodies and BiTEs (bispecific T-cell engagers), which are typically constructed by tandemly linking two single-chain variable fragments (scFvs)—one anti-TAA and one anti-CD3[2].

TCEs can also be engineered from different scFv combinations to create a wider range of formats and expanded functions. For example, scFvs from different sources can form BiTEs; BiTEs can be combined with a third scFv to make trispecific T-cell engager (TriTEs), or additional functional modules can be added to create tetraspecific T-cell engager (TetraTEs). A BiTE can be fused to the extracellular domain of PD‑1 to produce a checkpoint inhibitor T-cell engager (CiTE), or used in combination with a second molecule (e.g., anti‑CD28 × anti‑PD‑L1) to form a simultaneous multiple interaction T-cell engager (SMiTE). Molecular engineering at the VH–VL interface (such as interface mutations), shortening of interdomain linkers, or introduction of disulfide bonds have also given rise to other architectures like diabodies and tandem diabody and dual affinity retargeting (DARTs) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Classification of TCEs [2]

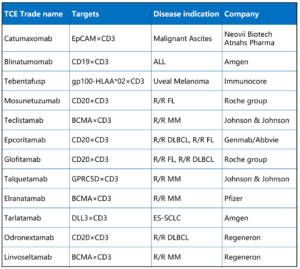

The global TCE therapy market has entered an accelerated phase. The first approved TCE, blinatumomab (CD19×CD3 BiTE) was approved in 2014 for relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and was later extended to the minimal residual disease (MRD) indication, becoming a benchmark therapy for hematologic malignancies. In 2024, tarlatamab (DLL3×CD3) was approved for small cell lung cancer, becoming the first approved TCE for a solid tumor. As of 2025, twelve TCE drugs have been approved worldwide, covering both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors (Table 1) [3].

Table 1. Globally approved TCE drugs [3]

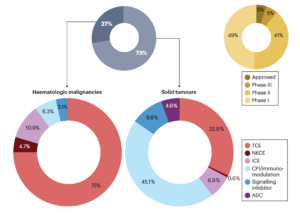

There are over 200 TCE candidates in development worldwide to date. Hematologic malignancies remain the primary focus, with core targets including CD19, CD20, and B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA). Among these indicated diseases are non‑Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and others. The solid tumor pipeline is expanding rapidly, with popular targets such as DLL3, Claudin 18.2, glypican-3 (GPC3), and PSMA, involving indications like lung, gastric, liver, and prostate cancers (Figure 3) [4, 5]

Beyond oncology, TCE applications are extending into autoimmune diseases. By depleting aberrant B or T cells, TCEs are being investigated in indications such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, with multiple pipelines already in clinical trials. By one estimate, there are over 20 TCE bispecific programs targeting autoimmune diseases worldwide, primarily directed at CD3/CD19, CD3/CD20, and CD3/BCMA. Additionally, the combination therapy pipeline is active: TCEs are being explored with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and oncolytic viruses, aiming to further enhance efficacy [4, 5].

Figure 3. Clinical trial pipelines of TCE therapy [4]

R&D strategies of TCE drugs

In vitro and in vivo pharmacology evaluation of TCEs

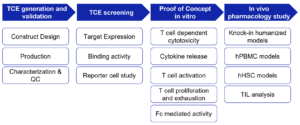

The preclinical pharmacological evaluation of TCEs can be broadly divided into molecular design and binding validation, in vitro functional characterization, and in vivo pharmacology assessment (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Workflow for preclinical in vitro and in vivo pharmacology evaluation of TCEs

Molecular design and binding validation of TCEs

The core design principle for TCEs is to build bispecific molecules and optimize molecular format, affinity, and specificity through engineering. Techniques such as SDS–PAGE, mass spectrometry, and size‑exclusion chromatography (SEC) are used to verify the binding activity, purity, and integrity of TCEs. Flow cytometry is employed to rapidly assess the ability of TCEs to activate T cells in reporter and tumor cell lines. For example, the Jurkat T‑cell line can be engineered to create a Jurkat‑NFAT‑Luc reporter that monitors activation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) pathway. Therefore, TCE activity can be evaluated by measuring NFAT signaling induced by CD3ε activation (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Working mechanism and detection examples of Jurkat-NFAT-Luc

In vitro functional characterization of TCEs

After TCE candidates have been selected, their anti-tumor activity, safety, and other characteristics need to be evaluated through in vitro functional validation. Key assessment metrics include:

- T cell activation: To confirm whether the TCE effectively activates T cells, use flow cytometry to measure expression of T cell activation markers (e.g., CD25, CD69).

- Cytokine release: Measure pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) to assess safety and efficacy. ELISA and multiplex platforms enable high-throughput, multi-analyte profiling to help predict cytokine release syndrome (CRS) risk.

- T cell-dependent cytotoxicity assays: Directly evaluating the ability of TCEs to induce T cell–mediated tumor cell killing is a core efficacy readout. In vitro co-culture assays—using calcein-release, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays, or reporter gene–based real-time systems—measure tumor cell death to verify targeted cytotoxic effects.

In vivo pharmacology evaluation of TCEs

Validating the in vivo anti-tumor activity of TCEs in animal models is a core part of preclinical assessment. Because TCEs act via human T cells and human target antigens—and most human antigens do not cross‑react with mouse homologs—humanized animal models are required to best mimic the human setting. Therefore, a series of in vivo pharmacology evaluations are primarily carried out using humanized mouse models.

Read more: OncoWuXi Express: Evaluation of T Cell Engagers – WuXi Biology

Clinical challenges for TCEs and pharmacokinetic response strategies

Despite rapid progress, TCE therapies still face multiple technical challenges, including frequent CRS, complex tumor microenvironment (TME), limited intratumoral T cell accessibility, tumor antigen loss, and lack of tumor antigen specificity [6, 7]. These challenges raise higher demands for clinical development of TCEs. Pharmacokinetic (PK) assessments, as a key segment in drug development, together with cytokine monitoring, immune phenotyping, and biomarker testing, can effectively address these issues.

PK assessments

To date, regulators have not issued product-specific guidance for TCEs. Therefore, PK studies for TCEs can refer to the FDA’s April 2019 draft guidance “Bispecific Antibody Development Programs” and the NMPA’s November 2022 “Technical Guidelines for Clinical Development of Bispecific Antibody Anti-tumor Drugs” [8, 9].

PK and anti-drug antibody (ADA) study design and bioanalysis for TCEs can also follow recommendations summarized in: Marketed Bispecific Antibodies and Their Pharmacokinetic Characteristics

Cytokine detection

In addition to routine PK and ADA assessments for bispecific antibodies, TCEs frequently induce CRS and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), which often co-occur [10]. Therefore, cytokine monitoring requires intensive sampling (pre-dose, within hours after the first and last doses, and at 24 hours, etc.) and measurement of key proinflammatory and regulatory cytokines (e.g., IL‑6, IL‑10, IFN‑γ, TNF‑α) [11]. Assay platforms include ELISA, MSD, Luminex, Simoa, or flow cytometry–based cytometric bead array (CBA); MSD is often preferred for its sensitivity (down to fg/mL) and broad dynamic range.

Immune phenotyping and immunogenicity assessment

To build reliable PK/PD models, concurrent monitoring of T cells and other immune cells (e.g., B cells, NK cells, monocytes), T cell activation (e.g., CD25, CD69) and proliferation, and target cell numbers is required to assess drug-mediated T cell activation and tumor cell lysis. Multiparameter flow cytometry panels enable dynamic immune phenotyping, providing both relative proportions and absolute counts [12].

Immunogenicity assessment should follow a tiered strategy: screening, validation, and titer determination, with neutralizing antibody (NAb) testing performed when necessary. Common assay platforms include MSD and ELISA.

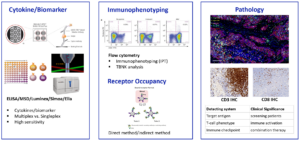

Biomarker assessments

Biomarker analysis is essential for monitoring the pharmacodynamics (PD) of TCEs and for evaluating correlations between drug exposure and clinical outcomes or immunogenicity. Typical biomarker assays for TCEs include:

- Flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry for immune cell phenotypes and spatial distribution;

- Single‑cell technologies for high‑resolution analysis of cellular heterogeneity;

- Multiplex immunoassays for cytokines and soluble factors;

- Imaging and digital pathology to further supplement efficacy and safety information.

Assay selection should be based on the specific Context of Use (CoU) and the Fit‑for‑Purpose (FFP) principle. Multi‑platform approaches are commonly adopted, with assurance that critical reagents and validation levels meet clinical requirements (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Biomarker analysis for TCE therapies

Future prospects for TCE therapies

TCE therapies have broad application prospects, with technological iterations and indication expansion advancing in parallel. In hematologic malignancies, they may become a standard approach for MRD clearance and further improve cure rates. In solid tumors, as highly specific targets are identified and combination strategies mature, TCEs could extend to prostate, lung, gastrointestinal, and other cancers. In the future, TCEs may not only serve as important monotherapies but also be combined with CAR‑T, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, oncolytic viruses, and other modalities to build multidimensional, synergistic anticancer strategies, bringing new hope to more cancer patients.

WuXi AppTec has accumulated extensive experience in TCE drug research and has established an end‑to‑end integrated TCE development platform, bringing together interdisciplinary teams and key technical capabilities. From target discovery, screening, in vitro and in vivo pharmacology, and PK/PD analysis to clinical biomarker testing, WuXi AppTec provides integrated services to partners to accelerate TCE drug development.

References:

- British Journal of Cancer (2021) 124:1037–1048.

- Cellular & Molecular Immunology (2024) 21:643–661;

- Haitong International, TCE bispecific industry research.

- Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024 Apr;23(4):301-319. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-024-00896-6

- https://www.pharmacodia.com/

- Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2020, 17(7): 418-434.

- British journal of cancer, 2021, 124(6): 1037-1048.

- Bispecific Antibody Development Programs Guidance for Industry, FDA

- Technical Guidelines for Clinical Development of Bispecific Antibody Anti-tumor Drugs, NMPA

- Frontiers in Immunology, 2025, 15: 1463915.

- http://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/blincyto

- Clinical Cancer Research, 2019, 25(13): 3921-3933.

- “Bispecific Antibody Development Programs” and the NMPA’s November 2022 “Technical Guidelines for Clinical Development of Bispecific Antibody Anti-tumor Drugs” [8, 9]. P

Related Content

Antibody-targeted therapies—including antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs), and degrader-antibody conjugates (DACs)—are reshaping precision medicine by enabling highly selective delivery...

VIEW RESOURCET-cell engagers (TCEs) are a class of bispecific antibodies that simultaneously bind tumor cells and T cells, activating T cells...

VIEW RESOURCE